*TRIGGER WARNING FOR SUGGESTION OF SEXUAL ASSAULT*

It’s important to find the perfect words.

Not everyone believes this, of course. People will often say that they don’t have the right words to explain or describe something, but in Georgiana’s experience, there is a perfect word for anything if only you’re willing to look hard enough for it.

Most people aren’t willing to make enough of an effort to find the perfect word. They’re happy to stick to the nouns, verbs and adjectives that they know, doing their best to to pinch and pull them into new shapes for new situations. This is, in Georgiana’s opinion, like trying to shove a square peg into a round hole – you might be able to do it, and you might even be able to convince yourself that it fits, but everyone else will still feel awkward and uncomfortable.

Right now, sitting at the kitchen table, she is testing out a new word. She does this by writing it out, letting her hand feel the truth of it as it guides the pen across the paper. First she prints COURTESAN in neat block letters across the top, then, after a moment’s consideration, she writes MY MOTHER IS A COURTESAN in elegant script half-way down the page. Georgiana’s handwriting is the best in her eighth-grade class. In fact, she won an award in a penmanship competition held at her school last year. Georgiana’s mother had snorted at this and said that it was ridiculous to give a prize for something no one cared about anymore, but Georgiana disagrees, and keeps the certificate they gave her in her second-best desk drawer. Penmanship, like baking bread or crocheting lace, is a skill that she has no immediate use for, but could very likely come in handy sometime in the unforeseeable future.

Georgiana slouches in her seat and stares at the paper, narrowing her eyes until her brow begins to furrow. My mother is a courtesan. Does it fit? Is it right? She tilts her head first to one side, then the other, then slowly lets her eyes drift out of focus. She’s feeling as though she’s getting quite close to something when the sound of her mother’s keys in the door interrupts her meditation. She quickly sits up and folds the paper neatly in half, then in half again before sliding it into the pocket of her skirt. A moment later, her mother, Peggy, appears in the kitchen and drops a quick kiss on the top of Georgiana’s head before heading over to refrigerator.

“Jesus Christ have I ever had a long day,” Peggy says to the carton of eggs on the second shelf. “I need about three drinks and then another drink on top of that. Honey, what do I want to drink? Do I want beer or wine?”

“I don’t know,” Georgiana answers, peevishly. “How should I know what you want? I’m not a mind-reader. You’re being stupid. You’re being stupid and you’re wasting energy by leaving the fridge open.”

“My thirteen-year-old daughter thinks I’m stupid. Quelle surprise. Next you’ll be insulting my taste in music.”

Georgiana twists a stray lock of hair around her finger as she watches her mother pour herself a glass of riesling.

“Mom,” she begins, keeping her voice carefully bored and distant. “Mom, what’s a courtesan?”

“Look it up. You know how to work a dictionary, and God knows that there are enough of them around here.”

“I tried, but I can’t find mine, and the door to your office is locked.”

This is patently untrue. Or rather, the lost dictionary is untrue, although Peggy’s office really is locked – it’s always best to add a little bit of truth into your lies, Georgiana has learned. It makes them that much more believable. With the right amount of fact and fiction, Georgiana knows that she can manipulate her mother into giving her some approximation of what the word means.

Not that she really wants a definition. What she wants is to see her mother’s reaction to the word.

Peggy sighs and rolls her eyes heavenward, as if deep in thought.

“Oh, I don’t know. I guess a courtesan is a woman who’s involved with a married man, and lives off the money and gifts he gives her. A sort of sex-worker, but not really in the way that we currently understand that term. She’s not exactly a prostitute, more like a professional mistress. I wouldn’t worry too much about it, though – it’s an old-fashioned word that no one really uses anymore.”

Like penmanship, Georgiana thinks, coolly maintaining her blank gaze as she watches her mother’s face. Is that a ripple of anxiety? Or embarrassment? It’s gone too soon for Georgiana to tell.

“Go change in to something nice,” says Peggy, ignoring her daughter’s stare. “We’re going to Eric’s for dinner,”

“But I’m already wearing a skirt,” Georgiana protests, conscious of the childish whine creeping into her voice.

“Well, I guess you’re going to have to put on a nicer skirt, then, aren’t you?”

And with that, her mother takes her drink into the living room and turns on the news, neatly ending the conversation before Georgiana can voice any other complaints. She sighs and begins to mount the stairs to her bedroom, dragging her feet as loudly and obnoxiously as possible.

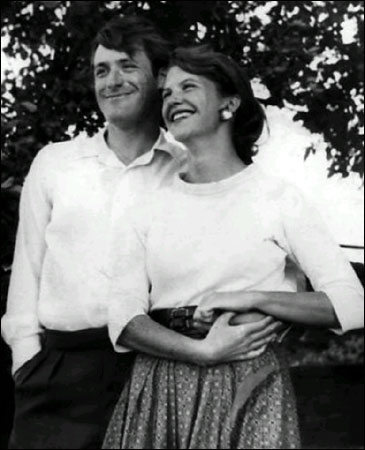

Eric is her mother’s boss, and Georgiana is certain that the two of them are an item, as her grandmother would say. Although Eric has been a part of Georgiana’s life for nearly as long as she can remember, she has only recently become aware of his true feelings for her mother. After reviewing all of the evidence, though, Georgiana can’t believe she’s been so blind for so long.

First of all, there’s the fact that Georgiana and her mother should not be able to afford to live the way that they do. Take this house, for example – their neighbours all have high-powered, lucrative careers, and the street is dotted with doctors, lawyers and hedge fund managers. Peggy, meanwhile, is the arts editor for the small, left-wing magazine that Eric owns. Georgiana has heard Eric say more than once that the magazine will never be profitable. How, then, are they able to own this house? How is Peggy able to keep Georgiana adequately clothed and fed? How does the liquor cabinet manage to stay so well stocked?

Next, there are all the evenings that Peggy spends at Eric’s house, supposedly “working”. But why do they need to meet at night? They see each other at the office all day long.

Georgiana’s mother used to leave her with a babysitter on the evenings when she had to “work late”, but lately she’s been bringing her daughter along, forcing her to dress nicely and pick her way through so-called gourmet meals cooked by Eric himself. But where is Eric’s wife? She is always noticeably absent during Georgiana’s visits to his house. The official story is that Eric’s wife is frequently out of town, “on business”, a reply that is both vague and entirely unsatisfying.

And then there are the swanky vacations her mother takes, alone, if you believe what she says. At least once a year Georgiana is dumped at her grandmother’s apartment, left to navigate her way through a sea of porcelain figurines and doilies, while her mother flies off to Barcelona, Rio de Janeiro, Milan. Last year it was Paris. Paris! Who goes to the most romantic city in the world by themselves? It’s clear that, when thoughtfully examined, Georgiana’s mother’s stories are totally lacking in credibility.

There are other, smaller things, as well. There’s the way that her mother behaves during Eric’s late night phone calls, like a giddy schoolgirl who suddenly has the attention of the cutest boy in the class. There’s the mysterious jumble of soft, velvety jewellery boxes in her mother’s underwear drawer, a stash that has grown alarmingly over the past several years. Worst of all, there’s the way that Georgiana’s mother treats Eric’s thoughts and ideas as though they come from God himself. If Georgiana has to hear “Eric thinks…” or “Eric feels…” one more time, she might slit her wrists.

Up until today, Georgiana hadn’t exactly been entirely certain that something was going on between her mother and Eric. The problem was that she’d been missing the right word to describe their relationship. She’d tried out fuck-friend, but that was crass and uncouth and not befitting of two adults involved in an adult situation. She’d also given the term mistress a whirl, but it was too dowdy, too boring. The word courtesan, on the other hand, has a lovely sing-song rhythm that Georgiana can’t get out of her head. It sounds vaguely foreign, and yet is a perfectly respectable English word. It’s elegant, rich, sensual, and bordering on obsolete.

Exactly the term she’s been waiting for.

After pulling on a suitably nice dress, Georgiana stands in front of her mirror and braids her coarse, wavy brown hair. She stares at herself critically, then suddenly leans in towards her reflection and viciously whispers, your mother’s a whore and you’re a stupid, ugly bitch.

She stays suspended in this position, her mouth so close to the glass that her breath appears as a fog. The edge of the bureau digs uncomfortably into her stomach, but she doesn’t mind. It actually feels sort of good, in a strange way. She waits until the funny ache bisecting her abdomen becomes more than she can stand, then pushes herself back and turns to rummage around in her closet, pulling out a pair of well-worn ballet flats.

She steps into her shoes and then sits on the edge of her bed, her face as blank and impassive as a mask.

The drive to Eric’s house is short and silent. Georgiana slides as far down in her seat as possible, fiddling with her braid, clenching the end of it between her mouth and her nose to make a mustache. Her mother, who hates driving, stares grimly at the road, her hands clenched in a death grip around the wheel from the moment they leave the house until they pull into Eric’s driveway. Eric, as always, is waiting for them, ready to open the door before they can even ring the bell.

“Peggy, you look lovely,” Eric says, kissing Georgiana’s mother on the cheek as he takes her coat. “I can’t believe you’re the same person who was having a minor meltdown three hours ago.”

“Oh God,” Peggy laughs, “wasn’t that a nightmare? I need a drink. I mean, another drink.”

“And the young Georgiana, beautiful as always,” Eric continues as Georgiana shrugs her jacket into his waiting hands.

She watches him out of the corner of her eye, saying nothing, listening for the crackle of her secret paper, stealthily transferred from one pocket to another, as he hangs her jacket in the closet. The noise is wonderfully satisfying.

Dinner is paella, and Georgiana spends the first half of the meal picking out the vegetables and moving them to the edge of the plate. Once that’s done, she concentrates on the edible parts of the dish. She has her first forkful of beans, rice and meat halfway to her mouth when Eric says,

“So, Georgiana, what are you studying these days?”

Georgiana is hovering between answering his question and stuffing her mouth full of food when Peggy replies for her.

“Don’t bother asking her, she’ll just tell you she doesn’t remember. Gigi never remembers what she’s learned at school, it’s one of her charming trademarks.”

Georgiana drops her fork with a clatter and turns on her mother.

“Don’t call me that,” she spits out.

“What, Gigi? Don’t be silly, I’ve always called you that.”

Peggy rolls her eyes at Eric, a gesture so entirely dismissive that Georgiana feels her face and chest flush with rage. Part of her knows that she will later feel embarrassed by what she’s about to say, but right now all she can feel is the rush of it, the exhilarating sense of being swept up in her anger.

“It’s a stupid name. It’s the name for a dog. It’s so humiliating. No one calls me that but you.”

“What do your friends call you?” asks Eric.

It’s such an unexpected question that Georgiana is immediately disarmed. She looks between Eric and her mother, their faces both calm and inquiring, and feels herself deflate.

“George,” she says, neglecting to mention the fact that she doesn’t have any friends. “It’s nice and short and gets right to the point.”

“Ah, yes, but what is the point?” Eric wonders aloud.

Georgiana, unable to tell if he’s laughing at her, ducks her head and takes refuge in her dinner. After a few minutes the centre of her dish is clear, leaving only a ring of vegetables.

“May I take my dessert in the library?” she asks, pushing her plate away.

Eric looks at Peggy, who shrugs her assent.

“It’s the chocolate cake on the counter in the kitchen,” he calls out as she beats a hasty retreat.

Or rather, she beats what only appears to be a hasty retreat. After she’s taken several loud steps towards the kitchen, Georgiana does a quick pirouette on the hardwood floor of the hall and then creeps back towards the dining room. She lingers at the edge of the pool of light spilling from the doorway, her mouth hanging half open as she strains to listen.

“God, I’m so sorry about that,” she hears her mother say. “She’s been so terrible lately. I’m trying so hard to just ignore her, because I know that at that age any attention is good attention, but Jesus Christ is it ever hard not to smack her sometimes.”

Eric murmurs something in response, but Georgiana can’t hear what it is.

She know that she should be upset over what her mother said, but instead she feels meanly glad. Good, she thinks, I’m glad she wants to smack me. I hope she does someday. I hope she does tomorrow.

Eavesdropping makes her hungry, and Georgiana feels entirely justified in cutting herself two enormous slices of cake. She carries her plate and a glass of milk down the dim hallway, towards the back of the house. The library, as Eric calls it, is really just a small-ish sitting room lined with bookshelves and furnished with two comfortably ancient armchairs, a couple of mismatched lamps and a sturdy but beat up old table. Most of the shelves are tall, reaching almost to the ceiling, but one of them is a squat, handsome case fronted by two neat little glass doors. This houses Eric’s collection of rare, first edition and out-of-print books, and Georgiana makes a beeline for it.

She spends an hour and a half with a 19th century medical encyclopedia, poring over woodcut drawings of syphilis infected genitalia and deformed fetuses. The pictures are fascinating and nauseating at the same time; looking at them makes Georgiana’s skin crawl, but she feels compelled to keep turning the pages. When she finally can’t take any more she closes the book and reverently places it back on the shelf. She feels strange, shivery and sweat-slicked, as though she’s just awoken from a bad dream. A thin, piercing headache is blooming right between her eyes.

She decides to go find her mother. Peggy and Eric will be upstairs, she knows, in the office, which is shinier and newer than the library. The office is probably where they do it. The thought makes Georgiana’s stomach turn over and causes her headache to spread until she can feel it pulsing through every vein, her scalp alive with tiny filaments of pain. The door to the office is closed, and Georgiana can hear her mother and Eric talking and laughing softly behind it. She is about to knock, about to tell her mother that she’s feeling sick and wants to go home, when suddenly she hears something. It’s her mother’s voice, contorted almost beyond recognition, groaning, sighing. Georgiana turns on her heel and runs to the bathroom.

She crouches over the toilet, sweat beading along her hairline. Her arms are shaking and her heart is pounding, sickness welling inside of her as she stares at the water. She wishes that her mother was there to hold her hair. She wishes that she’d never left the library, that she hadn’t been so rude at dinner, that she’d never started this whole stupid thing. Her breath comes in gasps, her stomach clenches hard and she gags, but nothing comes up. Her body, completely beyond her control, relaxes and then stiffens as she gags again and again. Tears begin to drip down her face, splashing into the toilet bowl beneath her.

Then, slowly, the nausea begins to recede, leaving her trembling and empty. When she feels steady enough, she pushes herself to her feet and runs cold water in the sink, splashing it on her face. Her head still aches, so she eases the elastic off the end of her braid and shakes her hair out until it frames her face like a mane. Between the cloud of her hair and her thin, pale face, the effect is distinctly pre-raphaelite, a wan Rosetti goddess, perhaps, or a despairing angel. She takes a step back and turns first one way, then the other. Her dress is made out of soft, stretchy fabric and she pulls it down over her shoulders, exposing both breasts. She lightly runs her hand across her nipples until they stand up like pencil erasers. Something begins to uncoil inside of her, like a vine, like a snake.

In her earlier haste to get into the bathroom she left the door ajar and now it begins to swing inward. Georgiana turns towards it, sort of almost accidentally forgetting to pull her dress back up. Eric is outlined in the doorway, bright against the dimness of the hall behind him. Georgiana gives him a look that she hopes is defiant, daring, her lashes lowered over what she thinks of as smouldering eyes. She expects him to be embarrassed, or even shocked at the sight of her breasts, but the expression on his face is frank, appraising. She shrinks back as he takes a step towards her, pulling her dress up over her chest. She is trembling again.

“I think I had too much cake,” she hears herself say, her voice childish and faltering. To her relief, he turns away.

She watches Eric leave the room, hears him call her mother. Peggy comes, lays a hand on her daughter’s forehead, then guides her out of the bathroom and down the stairs. Georgiana feels dreamily detached, like a spectator seated very far away from the action. She stands calmly as her mother rushes around, gathering her notebooks and folders together. She allows Peggy to help her into her coat and shoes while Eric hovers solicitously in the background.

At home, Peggy leads her daughter up to her bedroom and peels the dress off her feverish body.

“I’m sorry,” Georgiana says she burrows under her sheets, although she’s not sure what she’s apologizing for.

“My poor Gigi,” Peggy says, kissing the tip of her nose, “I forgive you, even if Eric and I were in the middle of something very important.”

Georgiana, her cheeks flushing pink and her mouth suddenly twisting into a snarl, uses the last of her strength to push herself up close to her mother’s face.

“I know what you do,” she spits, “I know what you and Eric do together. I know exactly what you are, and I think you’re revolting. You make me sick.”

A look of deep, frightened hurt spread’s across Peggy’s face, but is quickly replaced by a wintry smile.

“Go to sleep,” Peggy says calmly, “it’s late. Call me if you need anything.”

Georgiana sinks back, exhausted, feeling strangely empty now that’s she’s divulged her secret. Her mind is very still and quiet, the restless anger drained from it like pus from an abcess.

The next day, Peggy lets her daughter stay home from school, although she herself goes to work. Georgiana, for her part, enjoys her fever, the lightness and giddiness of it, and also the weakness. She spends the day in bed, eating grapes and reading comic books. The light outside is grey, soothing. She is safe, cocooned in her illness.

The day darkens into twilight, and her mother comes home. She brings a little tissue paper-wrapped package into her daughter’s room and lays it on her lap. Georgiana peels back the soft, thin layers slowly, revealing a small, lacquered wooden box. On the lid there is a young deer looking nervously over its shoulder, its eyes somehow both frightened and curious.

“It’s from Eric,” her mother says, perhaps a bit too casually, “he says that it reminded him of you. Don’t ask me why.”

Georgiana feels a small surge of triumph as she turns the box over in her hands. Triumph over what? She will have to untangle this later. For now, she contents herself with watching her mother’s face. Is that anxiety, creasing the edges around her mouth? Is that anger flashing somewhere deep in her eyes? Georgiana isn’t sure.

She settles back against her pillow and looks at the box, stroking her fingers along the deer’s back.

“Tell him thank you,” she says, finally. “Tell him that I know exactly what it means.”

Peggy gets up and leaves the room. Georgiana falls asleep, her flushed cheek pressed up against the cool painted wood. Outside her window, the streetlights come on and the world, for once, is very, very quiet.

Tags: being a teenager sucked ass, fiction, georgiana, literary pretentions, sexual assault, women, writing