I’ve had a weirdly emotional reaction to Pete Seeger’s death. Like, way more intense than I would have imagined. I mean, he was 94, right? That’s a good run. A really good run. And I haven’t listened to his music in years and years. Maybe not really – not seriously, anyway – since I was a teenager, back in the days when I wore daisy chains in my long, ratty hair and fancied myself to be some sort of hippie. Later, I abandoned him when I grew what I thought was a more sophisticated taste in music; his stuff started to seem too plain, too openly earnest, too babyish.

Today, though, I’ve been listening to his songs non-stop, and nearly every single one of them has made my eyes well up. These days, I’m all about plain and openly earnest. I’ll take someone who really means what they’re singing over the clever kid with the hollow, dead-eyed lyrics any day.

I guess I’ve always loved Pete Seeger; at the very least, I’ve been listening to his songs my entire life. When I was a little kid we sang “Where Have All The Flowers Gone” in Brownies and Girl Guides. When I was a bit older I liked “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and “If I Had A Hammer”. As a pretentious teenager who loved all things indie and underground, I fell in love with “Guantanamera” after it was used in Don McKellar’s 1998 film Last Night.

Last Night takes place during the final six hours of the world, which is about to end in a very polite Canadian apocalypse. The movie follows various story lines of characters, their paths often crossing and re-crossing, trying to make their last moments significant (or not). Sandra Oh plays a woman who’s desperately trying to get home to her husband, having gone out to buy the guns that they’re going to kill each other with just before the end comes – a sort of fuck you to the current circumstances, a way of taking control of their own deaths. But she can’t get home, because people are rioting in the streets, so she winds up at the apartment of a man played by Don McKellar. She asks to kill (and be killed) in lieu of her husband, as a way of keeping her word to him even if she can’t be with him. He agrees. And so the movie ends with them on his patio, guns pressed against each others’ heads, waiting until the last possible moment to pull the trigger. “Guantanamera” plays in the background.

But instead of shooting each other, they lower their hands, lean in, and kiss. And that too is a form of resistance, a way of saying fuck you to their circumstances.

And then the sun flares into an obliterating white, and everything stops.

I can’t watch it without crying. Still. Sixteen years later.

That scene might have been my first lesson in the ways that protest and resistance can look so different from how we might imagine them. It also may have been the first time I really understood that just because you know that there’s no possible way out, you still need to go down fighting.

Those were things that I learned from Pete Seeger’s music, too.

When I was a teenager, all music held some sort of lesson. I listened to music differently back then, in a way that seems uncomfortable, maybe almost painful now. There was an intensity of focus, a dizzying, full-body absorption that is almost totally lacking now. I studied songs that I loved as if they were going to be on the final exam; I learned them backwards and forwards, parsed their lyrics for meaning (especially meaning that seemed to apply specifically to my life), wrote them out over and over in the margins of my schoolwork. I lived those songs in a way that I just don’t anymore. I’m not sure when this stopped – sometime in my early twenties, I would guess – and I miss it. But maybe you just can’t sit with that kind of emotional intensity forever.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways that kids – teenagers especially – listen to music. And it’s almost like at that age, we listen as a way of learning how to interpret the world around us. Pop songs are, for teenagers, a sort of crash-course in understanding major life events that they haven’t yet experienced. I’d heard hundreds of songs about heartbreak before I ever had my heart broken; I’d listened to songs about death, about war, about inequality and resistance and protest long before actually living through those things. I sang along with songs about love, about its joys and its frightening fragility, years before falling in love. And so maybe that’s where the intensity comes from – we’re studying these three minute lessons packed full of unknown and highly romanticized human experiences, wanting so badly to know just exactly how they will feel when they finally happen to us.

When I was a teenager, I thought every song was about me. Even the ones I didn’t understand.

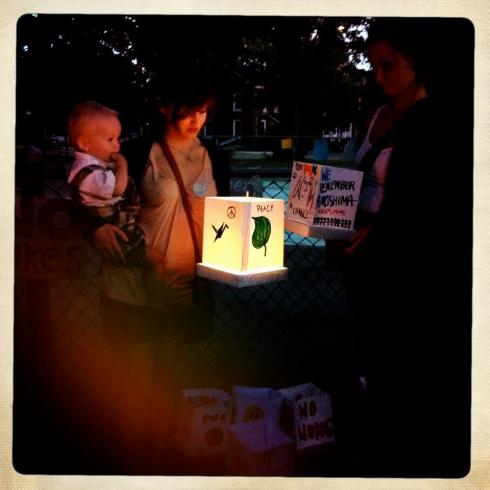

Pete Seeger’s songs seemed to be about me, too. Or at least about the great things that I would do – stand up against injustice, lead the charge against the oppressors, save the world. I wanted to be the girl who walked up to the line of soldiers, their guns, cold and oiled and gleaming, pointed straight at her, calmly offering them a daisy. I wanted to be so unafraid, even though I couldn’t imagine a time when I wasn’t always afraid of something or other.

And maybe I am that girl now, just a little bit. And if that’s true, then it’s at least in part because of songs, like the songs of Pete Seeger, and theatre and art and literature and oratory that have stirred my stupid sluggish soul and made me believe that I could and should be doing something more than I am. Because that’s the magic of Seeger’s music – that it can create community where there was none before, move the crowd to action, and actually affect change.

Music, if properly wielded, can start a revolution.

And maybe tonight I’m listening again with that same intensity that I used to have. And maybe I’m learning all over again about subjects that I know nothing about; subjects that yesterday I might have thought I was some sort of expert in.

So thank you, Pete, for all the revolutions, big and small, that you are responsible for. Thank you for the big thoughts framed in simple rhymes and simple chords. Thank you for the music you gave to the labour rallies, the civil rights movement, the anti-war protests. Thank you for reminding us that sometimes the written word can be ten times as powerful than a punch or a kick or a bullet. Thank you especially for your earnestness, because these days what I want more than anything is to be earnest. Thank you.

I hope it’s warm and peaceful wherever you. I hope that it’s dark, and that you’re finally able to take your rest. You’ve more than earned it.