I remember the first time it happened – it was shortly after Theo’s birth and I was still in the hospital. My mother and husband were in the room with me when the nurse came in to do something – maybe weigh him or help bathe him or check his vital signs. After she finished, she said, “all right, now I’ll give him back to mom,” and I was momentarily confused. Why was she handing my son off to my mother? Shouldn’t she give him to me or my husband?

And then I realized that she had, in fact, meant to give Theo back to me. Mom meant me. I was mom. My mother, meanwhile, had graduated to “Grandma.” The nurse left before I had the chance to tell her that my name was Anne, although if she’d really wanted to know that she could have just looked at my chart.

I got used to the name Mom, though, and faster than I’d thought I would. I started using it to refer to myself in the third person when I spoke to my son: “Mama loves you so much,” I would say to him. “Mama’s just going to change your diaper, and then you’ll be much more comfortable.” “Mama’s making your dinner, but don’t worry, she’ll be really fast!” “Ma-ma. Can you say ma-ma? Ma-ma. I’m your mama. Ma-ma.” By the time Theo was eight months old, he would howl “Maaaaaaaaa-maaaaaaaaa” every time he wanted me, and I felt a funny sense of triumph whenever I heard him call me. He knew my name. I was Mama.

I wasn’t the only one who referred to myself as “Mom” or “Mama” either. My husband did it whenever he was in front of our son, even when he was talking directly to me – after all, we wanted to keep things consistent and easy to understand for Theo, didn’t we? My mother did it, too. So did my sisters. And as my son got older and we started making the rounds of playgroups and library programs and sing-alongs, the other parents (almost exclusively women) referred to me as “Theo’s mom.” Not that I was any better – I didn’t know any of their names, either. We were all just so-and-so’s mom, as if that were our name or our job title or maybe the most fascinating fact about us.

Admittedly, there were a lot of things in my life that made me feel as if being a mother was the most fascinating thing about me, or at least the best, most noble thing about me. Strangers smiled at me, and offered me their seat on the bus. People working in customer service were more polite and attentive, whereas before I felt as if I’d often been brushed off. Everyone took me more seriously. It was as if by giving birth I’d somehow gained some strange kind of respectability. I wasn’t just that weird girl who talked too much and cried easily; I wasn’t just another person who had never reached their full potential. I was a mother, and according to a lot of people I’d fulfilled exactly as much of my potential as I needed to. And while on some level that fact was embarrassingly gratifying, mostly because I’d never felt so much societal approval before, underneath that gratification was a restless, howling anxiety.

I wasn’t the only one in our household to be given a new title, of course. My husband became “Daddy,” a name that also carries some baggage with it. But he didn’t seem to feel as if he was losing himself, the way that I did – and it does seem to bear pointing out that our circumstances were vastly different. Every day, while I stayed at home with our son, my husband went to work. Every day, while I sat on the couch and cried over how fucking hard breastfeeding was, while I took a deep breath and tried not to scream with frustration because my kid was inconsolably exhausted but absolutely would not nap, while I stripped off yet another urine-soaked onesie and brightly-coloured cloth diaper only to watch in horror as my son chose that exact moment to unleash a jet of poop, my husband went back to the Land of the Adults, a country that we both called home but from which I had temporarily been exiled. Every day, while I opened my laptop and tried yet again – through frighteningly hive-minded online parenting communities, frantic status updates on Facebook, and emails to my family – to find the training manual for my overwhelming new job, my husband went back to his same old job, where he could take hour-long lunches and everyone called him by his real name.

No. It wasn’t the same thing at all.

I tried not to feel like I’d somehow lost something, because how could I have lost something? I hadn’t lost anything; I was still the same person, wasn’t I? Even if I felt like I’d lost myself, I was clearly still there. I still existed. On top of that, it seemed unbelievably selfish to frame it in terms of “loss” when, in fact, I’d gained a perfect baby – especially when several of my friends were struggling in various ways to become parents. And I’d wanted this, hadn’t I? Becoming a mother had been my choice. So how could I complain?

Another layer to my unease lay in the fact that if I felt like I’d lost some part of identity, then had my mother experienced the same thing when she’d given birth to me? It seemed impossible that she had ever been anything other than what she was, namely my mother; and yet that selfish feeling of impossibility was almost certainly evidence of the part that I had played in who she had become. For a long time I’d thought that I would never grow up to be my mother, because my mother’s life had always seemed so constrained and limited. Now I saw that I was the one who had limited it.

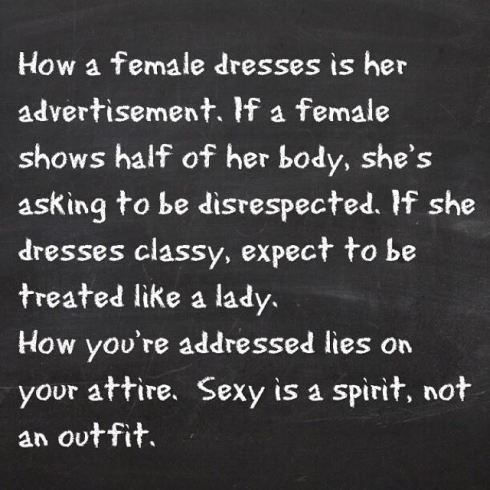

Maybe saying that becoming a mother was my choice wasn’t quite the right way to put it. Maybe it’s more accurate to say that I chose to become a parent, and then society gave me the label “mother” with all of its loaded associations. After all, what is there specifically about being a woman that says that you have to lose yourself completely once you have a kid? Isn’t it possible that if we lived in a world that treated motherhood and fatherhood equally – a world where we called it parental leave instead of maternity leave, a world that was just as accepting of stay-at-home fathers as it was of stay-at-home mothers, a world where women couldn’t expect their wage to decrease by 4% for every child they have – then women wouldn’t feel as if having children was a deeply personal sacrifice?

I mean, of course you have to give some stuff up once you have a child. I’m not saying that your life should stay exactly the same. But you shouldn’t have to sacrifice yourself.