On Friday night, Matt and I went on a For Real Date to see the Frida & Diego exhibit at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Frida Kahlo is probably my all-time favourite painter; I have literally been counting down the days until this show opened.

I have friends who know a lot more about galleries and exhibiting art than I do. They make intelligent remarks like, I wasn’t thrilled with how this collection was curated, or, I thought the lighting in the third room really brought an interesting tone to the whole show. I hope you’re not here to read anything like that, because I honestly know very little about how galleries should or shouldn’t display art. On top of that, I’ve been waiting at least ten years to see Frida’s works in person, so the AGO could probably have held the show in a dank basement room lit by a single 60-watt bulb and I would still have been thrilled.

The Frida & Diego exhibit is an assortment of Kahlo and Rivera’s works, often juxtaposed in interesting ways. The first room is filled with paintings from Rivera’s days as an art student in Madrid and Paris; they’re neat because you can clearly see the time he spent dabbling in Realism, Cubism and Post-Impressionism. That being said, although his early paintings are clearly technically very good, for the most part they aren’t terribly interesting or different.

Three of Rivera’s earlier works

The second room is more still more Rivera, and includes a reproduction of one his most famous murals, The Arsenal, starring Frida as a communist bad-ass distributing weapons to the people.

Finally, in the third room, we begin seeing some of Kahlo’s work. I dragged Matt from painting to painting, drinking in the familiar scenes and pointing out details that I was noticing for the first time. I began to look at the dates of the paintings, trying to slot them into the narrative of her life, and in doing so I was struck me was how young she was. I mean, I’d always known that she’d died young, but for the first time I realized that she’d been painting masterpieces when she was younger than me.

Frida was born in 1907 (although she often gave her birthdate as 1910 in order to coincide with the beginning of the Mexican Revolution), and was the third of four daughters born to Guillermo and Mathilde Kahlo. Frida’s father came from a German-Jewish background, and her mother was of Spanish and Indigenous descent; Frida was fascinated by her parents’ history, and her own mixed heritage would come to play an important part in her art. In 1927, at the age of 20, she already considered herself to be a professional painter. She married Diego Rivera in 1929.

Her seminal painting Henry Ford Hospital, which depicts a bed-ridden Kahlo shortly after a traumatic miscarriage, dates from 1932. I kept looking at it and thinking, she was only 25 when she went through that. She was only 25 when she painted that.

Henry Ford Hospital, 1932

Kahlo’s 1932 miscarriage (which was the second of three that she suffered) was by no means the first time she’d experienced pain or hardship in her life. At the age of six she was stricken with polio and, although she made a near-full recovery, for the rest of life her left leg remained smaller and weaker than the right. Then, at the age of 18, she was riding a bus that collided with a tram car. She suffered massive injuries, including three breaks in her spinal column, a shattered pelvis and multiple other broken bones. She was also skewered by a steel handrail, which pierced her abdomen and came out her vagina. She later told her family that the handrail took her virginity (totally untrue, by the way).

Her boyfriend at the time, Alejandro Arias, described the scene of accident to Kahlo biographer Hayden Herrera in gory but also hauntingly beautiful terms:

“Something strange had happened. Frida was totally nude. The collision had unfastened her clothes. Someone on the bus, probably a house painter, had been carrying a packet of powdered gold. This package broke, and the gold fell all over the bleeding body of Frida. When people saw her they cried, ‘La bailarina, la bailarina!‘ With the gold on her red, bloody body, they thought she was a dancer.” – Hayden Herrera, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo

Frida suffered from the effects of that accident for the rest of her life. She underwent 35 separate surgeries in an attempt to repair the damage. The handrail had gone through her uterus, leaving her unable to carry a baby to term; this was especially heartbreaking, as Frida wanted almost more than anything to have a child with Diego.

Part of the reason that Kahlo wanted to have Rivera’s child is that she thought it would bind them together in a way that marriage on its own couldn’t. Diego was a known womanizer, and continued to sleep with other women even after he married Frida. Deeply hurt by Diego’s infidelity, as well as her own inability to carry a child (which would have been Rivera’s fifth, as he had four others by past wives and mistresses), Frida began to have her own affairs with both men and women. Throughout the rest of her life Frida had dozens of lovers, including, purportedly, Josephine Baker and Leon Trotsky.

The fact that both Frida and Diego had numerous love affairs over the course of their marriage (which lasted from 1929 until 1939, then resumed in 1940 and lasted until Frida’s death in 1954), and the fact that both of them slept with women, makes the AGO’s juxtaposition of the two portraits of Natasha Gelman, one each by Kahlo and Rivera, all the more interesting.

Kahlo’s portrait of Gelman, 1943

- Rivera’s portrait of Gelman, 1943

In Kahlo’s portrait, Gelman is unsmiling, even stern, while Rivera’s version of Gelman is languorous and sensual, a small smile playing on her lips. Kahlo’s Gelman seems matriarchal, perhaps even a bit masculine, with a square jaw and intently serious gaze. Rivera’s Gelman, on the other hand, takes on a more traditionally feminine appearance, both in the softness of her face and the curve of her hip and leg. Simply put, Kahlo’s version of Gelman looks like a fucking awesome boss lady, and Rivera’s looks like someone he would want to sleep with.

I’m no expert, but I feel like these two pictures say a lot about how Kahlo and Rivera view women, both in general and as prospective partners.

It was also fascinating to see a selection of works by Kahlo that were inspired by her miscarriages hung alongside a series of paintings by Rivera depicting mothers of young children. I can’t imagine how heartbreakingly difficult it must have been for Frida to know that Diego had children with other women; how at times she must have felt inferior and defective because she could bring another “Little Diego” into the world.

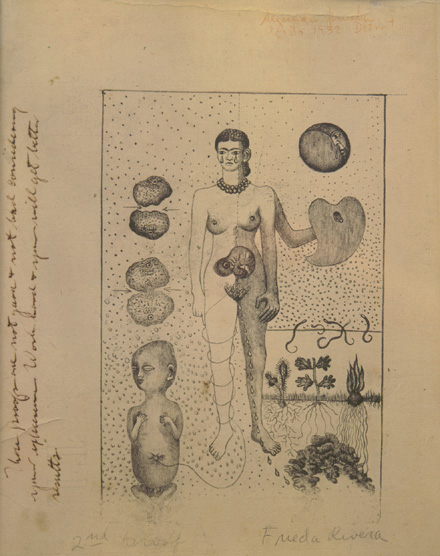

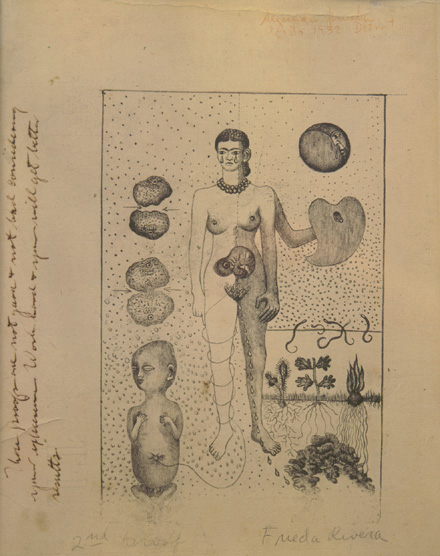

Frida Kahlo – Frida Y El Aborto

Diego Rivera – Maternidad

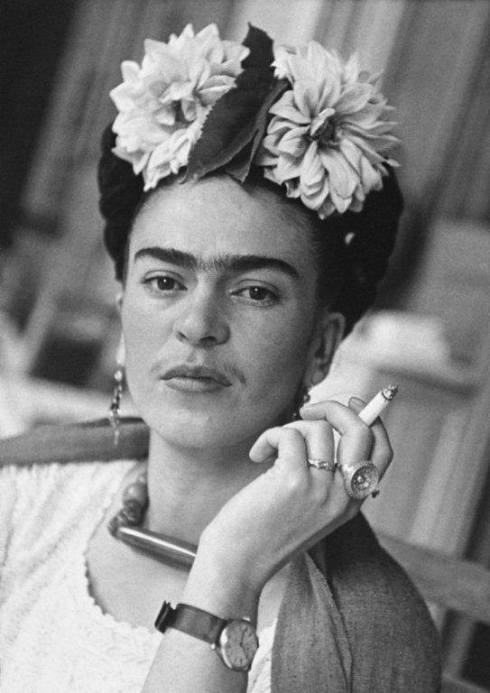

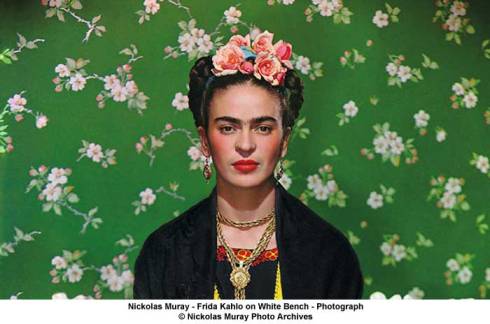

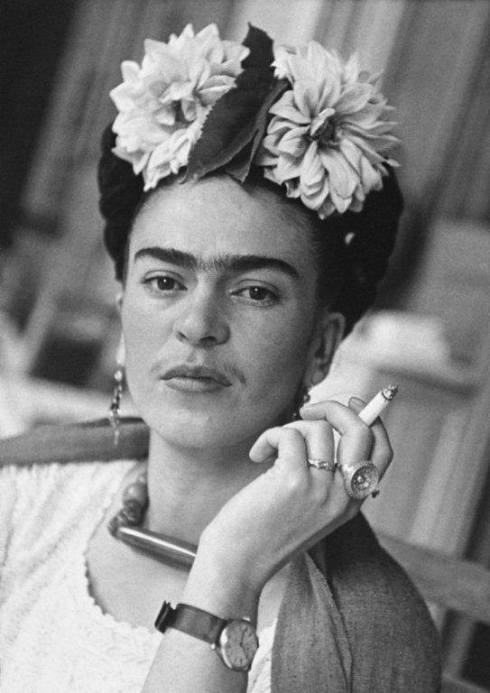

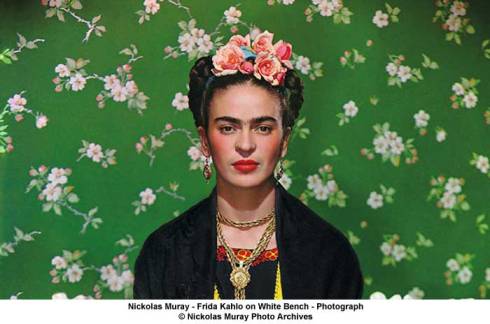

One of my favourite parts of the exhibit was the room that contained media by other people of Frida and Diego. There were photographs on the walls, and a black and white video of the couple was playing on the large screen. Of all the photographs that were included in this show, my favourites by far were those taken by Nickolas Muray, Frida’s former-lover-turned-good-friend.

Nickolas Muray – Frida In The Dining Area Coyoacan With Cigarette

Nickolas Muray – Frida Kahlo on White Bench

In many of Muray’s pictures, Frida is looking straight into the camera. Her gaze is intimate, disarming; her eyes bore into you, and it seems like she’s just about to speak. In some of the pictures, her mouth is quirked into a half-smile, as if she and the viewer share some kind of inside joke. No one else really understands, her expression tells you, no one but you and I, that is. You feel complicit in something, but you’re not sure what.

The video was just as wonderfully intimate as Muray’s photographs. In it, Frida and Diego are shown at home, in the courtyard of Casa Azul. In their every movement, their every look and touch, their tenderness for each other is evident. At one point Frida reaches out to take Diego’s hand and place it on her cheek; her expression when she feels his palm against her face is like that of a cat sleeping in a puddle of sunlight.

On the whole, the show is wonderful. My only issue with it (aside from the fact that several of my favourite Kahlo pieces are missing) is the subtitle, Passion, Politics and Painting. The advertising done for the show, which includes the slogan, “He painted for the people. She painted to survive.” makes it seem as though the politics were all Diego’s and the passion all Frida’s. Even within the exhibit, there is much attention given to Diego’s political activities, and only a few brief mentions of Frida’s membership in Mexico’s communist party.

To say that Frida wasn’t political is a mistake; she was deeply political, and on a very personal level. The way she dressed was political, as was the way she behaved, not to mention her art. In a time when the Western culture and its concept of beauty was beginning to take over Mexico’s cultural landscape, Frida, in many ways, turned her back on it and embraced her Mexican of her heritage. She traded the European clothing of her childhood for traditional Spanish and Indigenous garb. She refused to alter her unibrow, and, in fact, accentuated it and her mustache in her self-portraits. She was known to be unfaithful to her (equally if not moreso unfaithful) husband, and took women as lovers. Perhaps most importantly, she painted and talked about things that no one had ever publicly discussed before: things like miscarriage, infertility, sexuality, violence against women and infidelity.

In many ways, she started conversations that we’re still having today.

Plus, how can you think someone is not political when they paint this on their own body cast?

Kahlo’s Body Cast with Hammer & Sickle and Fetus

I wish I could explain to you how and why I love Frida so much. I keep starting sentences and then deleting them; all the words I pick seem fumbling and wrong, the emotion either overwrought and clumsy or woefully lacking. Even the things that I’ve already written here seem stilted and lifeless, which is the opposite of what writing about Kahlo’s life should be.

I guess that the best thing that I could say would be this: Frida had a really hard fucking life, but instead of backing down, she took all of her pain and heartache and turned it into something beautiful. She lived and she worked and she loved and she challenged and she pushed and in the end, I think, she won.

***

Frida died of a pulmonary embolism in 1954, at the age of 47. I mean, 47. Fuck. She was so heartbreakingly young. Shortly before her death, she wrote the following in her diary:

“I hope the exit is joyful — and I hope never to return — Frida”

I hope that wherever you are now, Frida, you are joyful. I hope that you’re finally free from pain. Most of all, I hope that Diego is there with you.*

Frida and Diego ofrendas

The exhibit closes with a pair of ofrenda depicting Frida and Diego. An ofrenda is a type of Mexican home altar, most often built for el Dia de los Muertos (The Day of the Dead). An ofrenda typically represents a dead family member, and is honoured by the living with traditional offerings of food and flowers. On October 24th, Mexican artist Carlomagno Pedro Martinez will construct an ofrenda in the gallery space; visitors on that day will be given art supplies and encouraged to contribute drawings and words to Martinez’s work. The installation (along with the entire exhibit) will be on display until January 20th, 2013.

*And that he’s, like, hanging out with you and not busy macking on angels or whatever (I am JUST SAYING, okay?)

p.s. In case you weren’t sure how I felt about Frida Kahlo in general, and this exhibit in particular, here is a visual aid for you:

Tags: ago, art, art gallery of ontario, diego rivera, feminism!, frida, frida kahlo, history, matt, painting, relationships, women, writing