This will be the final instalment of my totally unplanned Bullying Trilogy (seriously, it started out with me just wanting to talk about clothes).

After I made my last post talking about how I was bullied in my teens, my friend Audra asked if I’d read this 2011 article from New York Times, Bullying As True Drama. In fact, I had read it when it first came out and hadn’t really given it much thought. Re-reading it, though, I found myself nodding and muttering, yes, yes, yes under my breath.

So much of this article hits home for me. This part, for instance:

“Many teenagers who are bullied can’t emotionally afford to identify as victims, and young people who bully others rarely see themselves as perpetrators. For a teenager to recognize herself or himself in the adult language of bullying carries social and psychological costs. It requires acknowledging oneself as either powerless or abusive.”

Or this:

“While teenagers denounced bullying, they — especially girls — would describe a host of interpersonal conflicts playing out in their lives as “drama.”

At first, we thought drama was simply an umbrella term, referring to varying forms of bullying, joking around, minor skirmishes between friends, breakups and makeups, and gossip. We thought teenagers viewed bullying as a form of drama. But we realized the two are quite distinct. Drama was not a show for us, but rather a protective mechanism for them.”

And especially this:

“Teenagers want to see themselves as in control of their own lives; their reputations are important. Admitting that they’re being bullied, or worse, that they are bullies, slots them into a narrative that’s disempowering and makes them feel weak and childish.”

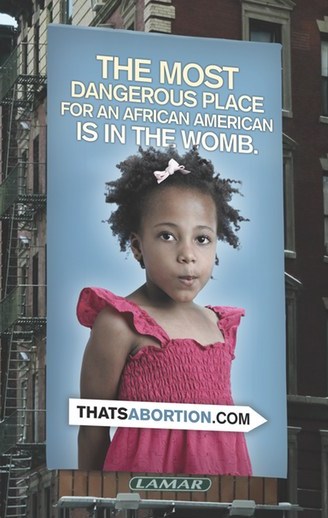

Like I said in my last post, bullies can smell a victim. The minute that you admit to yourself or to others that you’re being victimized, then I guarantee you that, barring serious intervention, the bullying will get worse. To make matters even more difficult, many kids (and adults) don’t realize that they’re bullies; this behaviour is so ingrained in our culture that it seems downright normal. I’m certain that most of the kids inflicting “drama” on others have, at some point, been on the receiving end of “drama”. To them, it’s an unpleasant but ultimately unavoidable part of life.

We also need to realize that the ways in which bullying happens have changed; it often occurs online, or through texting; it’s not always public. This, then, is where I think David Dickson, chairman of the Bullying Prevention Initiative of California, really misses the mark with definition of bullying as happening, “typically in a social setting in front of other people“. That definition certainly doesn’t hold true today; in fact, I’m not sure that it’s ever been accurate.

One of the best literary instances of bullying that I can think of is the torment that Elaine Risley goes through at the hands of her so-called “best friends” in Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye. Though all three of her friends are party to the bullying, few outside of that group know what’s happening. In fact, Elaine is pretty clear about the fact, were she to tell anyone about being bullied, she would feel as though she were breaking some kind of sacred code:

“Whatever is going on is going on in secret, among the four of us only. Secrecy is important… to violate it would be the greatest, the irreparable sin.”

A few adults in Elaine’s life seem to have some inclination as to what’s going on; she hears the mother of one of her friends saying that she deserves to be bullied because she’s a “heathen”, and, several years after the bullying occurs, Elaine’s mother makes a vague reference to the girls giving Elaine a “bad time”. Those instances aside, none of the grown-ups seem to know or understand the severity of what’s happening. The three girls are at Elaine’s school, and one of them is even in her class, but none of the teachers seem to notice that anything is amiss with their relationship; even her peers see only a group of “best friends” and nothing more.

Based on all the above, I wouldn’t say that Elaine’s bullying is public; in fact, her tormentors are very careful to maintain the façade of friendship that they’ve built up. Does that mean that it’s not bullying? Elaine is certainly emotionally, mentally and physically scarred by what she’s going through; not only are her self-confidence and happiness eroded to the point of non-existence, she also begins experiencing symptoms of severe anxiety such as fevers, stomach aches and tendencies of self-harm (among other things, she begins biting her fingers, and pulling patches of skin off her lips and the soles of her feet).

Another important thing to note is that, much like the girls mentioned in the Times article, neither Elaine, her friends, nor the adults in her life ever use the term bullying. Instead, they use euphemisms like giving her a hard time. At one point Elaine’s mother even tells her not to let the other girls push her around, and not to be spineless, as if that’s any kind of helpful advice. So the message that Elaine receives both from her “friends” and the adults in her life is that the way she’s being treated is her own fault.

This, then, helps explain why, when the balance of power shifts between Elaine and her “friend” Cordelia, Elaine begins to bully her back. While Cordelia spent most of grade school bullying Elaine, Elaine turns around and spends much of high school treating Cordelia equally terribly. In her mind, though, she’s not a bully; she can’t be, because, in Elaine’s eyes and the eyes of the world, her “friends” from elementary school weren’t bullies either.

At one point, when things are at their worst, Elaine’s mother says to her,

“I wish I knew what to do.”

And that, that right there, is often the hardest pill for both adults and teenagers to swallow – the fact that when bullying or “drama” occurs, the adults involved often just don’t know what to do.

I’m going to go out on a limb here and guess that part of the reason teens started using the term “drama” to sort of re-brand bullying was the realization that, possibly for the first time in their lives, the adults around them had no clue how to stop them from hurting. So the term “drama” isn’t just a protective mechanism for the kids themselves; it’s also their way of protecting their parents and teachers, a way of reassuring them that it’s okay that they have no idea how to help because it’s nothing, just drama, and their help isn’t needed.

Matt and I were both bullied when we were younger, and because of that we’ve talked extensively about what we would do if Theo was ever bullied. I would like to say that we’ve come up with an awesome plan but, really, we haven’t. If things were ever to get really bad and Theo were to express a desire to change schools, Matt would prefer to go ahead and do that, whereas I would rather that he learn to work things through with his peers rather than running away. Of course, Matt doesn’t know what he would do if things were equally bad at Theo’s new school, and I have no idea how Theo is supposed to learn to rationally work things through with a bunch of hormonally-crazed teenagers.

I think, though, that at the end of the day that Times article has it right; instead of focussing on the “negative framing” of bullying, we need to work towards teaching our kids what healthy peer relationships look like and how to be good digital citizens. We need to teach our kids empathy and the ability to recognize when “drama” has gone too far. We need to find ways to empower our kids instead of making them feel weak or victimized.

I know, I know, this is a lot of talk without a lot of substance to back it up, but hey – I’ve hopefully got a few more years to figure it out. And while I’m teaching Theo how to be a smart, confident, independent person, I’ve got him to teach me how to be a thoughtful, wise and effective parent. So far, I think we’re both doing a pretty okay job.