There are few things in life that make as incredibly, blindly, need-to-punch-a-wall-right-now angry as Roman Polanski. Any mention of him makes my blood boil; even just having someone tell me about one of his movies leads to me shouting obscenities for a significant length of time. So imagine how I felt when I saw the following headline on Yahoo News:

“Former teen who had sex with Polanski writing book”

The article then goes on to say that,

“Polanski … fled the country in 1978 on the eve of being sentenced for unlawful sexual intercourse with Geimer, 13 at the time”

Let me just sit here a moment while your head explodes a little.

Let’s get a few things straight: Roman Polanski did not have “unlawful sexual intercourse” with a 13 year old girl – he raped her. The victim, Samantha Geimer, testified that the sex was not consensual; in fact, according to her testimony, she explicitly told him no. And you know what? Even if she hadn’t told him no, it would still have been rape. Even if Polanski hadn’t given her alcohol it would have been rape; even if he hadn’t drugged her it would have been rape; even if she had said yes it would have been rape.

Know why? Because she, a vulnerable 13 year old girl faced with a millionaire film director in his 40s, was subject to an extreme imbalance of power. As Geimer said in her testimony,

“We were alone and I didn’t know what else would happen if I made a scene. So I was just scared, and after giving some resistance, I figured well, I guess I’ll get to come home after this”

She didn’t fucking know what else would happen if she made a scene. Here was a girl, who had been given champagne and qaaludes, who was faced with unwanted sexual advances from a man more than three times her age, a man who wouldn’t take no for an answer. She was afraid for her life.

What Polanski did was rape. I don’t care that he was later offered a plea bargain (because Geimer’s lawyer did not want her to have to endure a trial) that lessened his charges from rape by use of drugs, perversion, sodomy, lewd and lascivious act upon a child under 14, and furnishing a controlled substance to a minor to the much shorter and nicer-sounding unlawful sexual intercourse. I don’t care that the only thing Polanski plead guilty to was said charge of unlawful sexual intercourse. I just don’t care.

Let’s be really clear on one thing here:

Roman Polanski drugged and raped a 13 year old girl.

Roman Polanski raped a 13 year old, plead guilty to “unlawful sexual intercourse” and, when he realized that he was facing jail time, fled the country. He continued to make movies, continued to receive the financial backing and participation of major studios and A-list movie stars, married a woman 33 years his junior, and had two children. He has suffered basically zero consequences because of what he did.

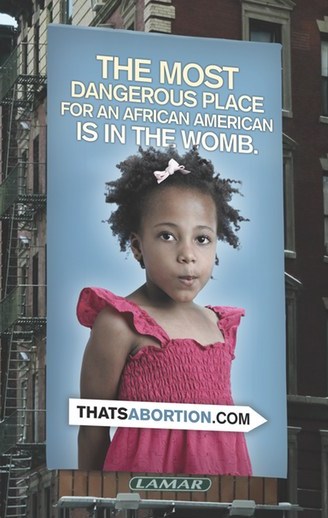

This is what rape culture looks like.

Rape culture means that we refer to children who were raped by celebrities as “former teens” (what the fuck does that even mean?), and use terms like “unlawful sexual intercourse” instead of “rape” when describing what happened to them.

Rape culture means that Johnny Depp, Adrien Brody, Ewan McGregor, Pierce Brosnan, Kim Catrall, Jodie Foster, Kate Winslet, Helen Bonham Carter Walter Matthau, Harrison Ford, Kristin Scott Thomas, Sigourney Weaver and Ben Kingsley are, by appearing in and promoting Polanski’s films, all tacitly saying that they are just fine with the fact that he raped a 13 year old girl.

Rape culture means that a lengthy list of celebrities, many of whom I used to admire, have publicly defended Polanski.

Rape culture means that Whoopi Goldberg has gone on record saying that what happened wasn’t rape rape.

Rape culture means that so many people are willing to ignore what Polanski did because they just want to sit back and enjoy his movies without having to feel guilty.

Rape culture means that a young girl’s life was destroyed, while her rapist went on to win Oscars for his movies.

Rape culture means that we live in a world where celebrities, the media, and even our friends and family normalize, excuse and condone rape to the point where a rapist can continue to live a happy, normal life with very limited consequences.

Look, I’m not normally the type of person who can’t dissociate an artist from their art; I still love Picasso, even though he treated women terribly. Ditto for Ernest Hemingway. Truman Capote was pretty awful, especially to my girl Harper Lee, but I can still read Breakfast At Tiffany’s and love every word of it. I recognize that the art and beauty a person creates are separate from who they are.

But I will never, ever see a Polanski film. I will not in any way, shape, or form give my tacit support for what he did.

I will not knowingly participate in rape culture.

Edited to add: A few people have brought up the 1969 murder of Polanski’s pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, and the fact that he is a Holocaust survivor.

A bit of clarification – I am aware of both those facts. I do not like the fact that people use them as an excuse for what he did. I am certain that Polanski was deeply, irreparably damaged by these events. That being said, he made a CHOICE to rape Samantha Geimer. He was conscious of his actions; he even underwent a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation after his arrest. I do not think his past can be used as an excuse or justification.